Most every ATW guest has been waiting for this day for the entire time we have been on the ship. Going through the Panama Canal is a bit of a rite of passage. It is a big deal to most everyone who has ever had the opportunity, sort of like the first time you cross the equator. In fact, most of the people that booked this last segment from Los Angeles to Miami did so specifically to transit this most important and impressive engineering achievement.

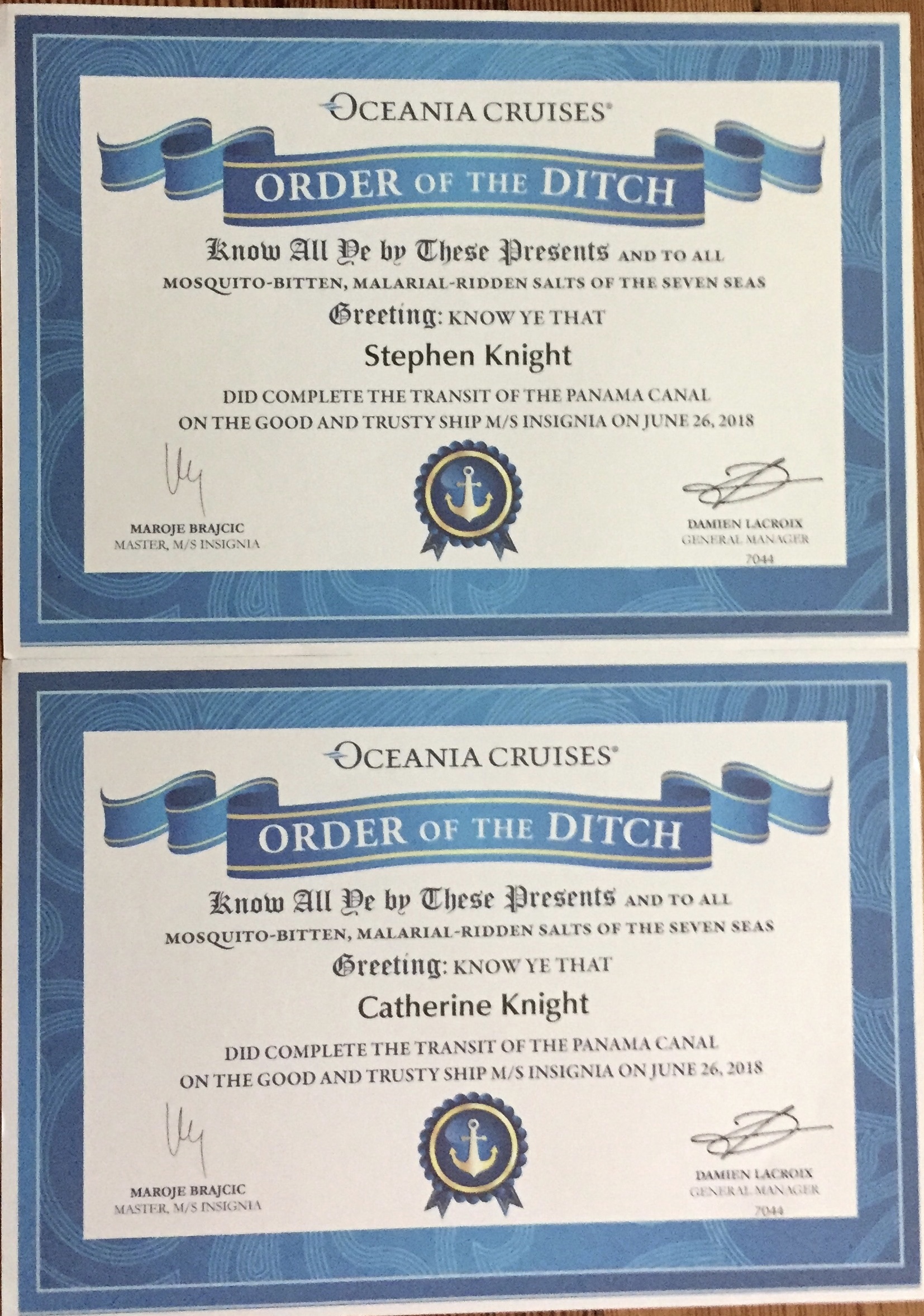

As mentioned before, for days now we have been watching a couple of documentaries on the building of the canal. Oceania Cruises had a showing of Hydrotech about the canal expansion. Peter Croyle had an excellent lecture on the subject. Captain Brajcic explained days ago that Insignia had a reservation to transit the canal at a particular time. Cruise Director Ray and General Manager Damien will spend the entire day off the ship creating a video of the ship’s passage through the Canal. Everybody is ready!

As part of our individual preparations, Cathy has asked our friend Patricia Watt if we could spend some time in her stateroom and on her veranda on this day because she has Stateroom 6001 which faces the bow on Deck 6, which will be a great place to watch the action and take photos. Not only does she graciously say yes (at least three months ago) but plans an open house for some of her many friends to join her on that day.

In most of our posts, I try to include statistics and other historical information I have gotten from our guides, from Wikipedia and from other sources. There is no point in doing that in discussing the Panama Canal. I went on to YouTube to see if they had the David McCullough documentary I mentioned in a previous post, and I fell down the YouTube Rabbit Hole. There are dozens and dozens of videos on the subject, including a two-hour PBS American Experience documentary. I did not find the David McCullough one, but we saw the American Experience one also and it is very good. YouTube includes lots of time-lapse videos of a transit. I am hoping to include a couple of 30-second time-lapse videos I took which are of very amateur quality, so I highly recommend going on YouTube for more on the subject if it interests you.

We learn the Transit Schedule the evening before when we receive our Oceania Cruises Currents for today. We are scheduled to enter the first set of locks, the Miraflores Locks, at 8:05. We are scheduled to depart the last set of locks, the Gatun Locks, at 3:50pm. All of that is subject to change, and we learn early today that our actual arrival at the Miraflores Locks will be 9:00am.

Our day begins at 5:45am when the lovely Room Service Steward Jay brings the daily coffee and croissant. She is as psyched as everyone else on the ship. At 6:00am, the pilot boat Wahoo XX pulls up to the ship almost right under our stateroom. The Panama Canal Authority of course has a pilot on the bridge of every ship to supervise the transit. Today a few other matters are addressed. A guide from the Panama Canal Commission, Jose Fernandez, also boards the ship with the pilot. He will spend the day on Deck 9 giving information about the canal and what is going on as we go through the lock system. His remarks will also be on the public address system and on Channel 4, which is the Bridge Cam channel.

The Wahoo XX also brings 15 cases of Panama beer ordered by the ship, a box of brochures to be delivered to each stateroom, and, for whatever reason, four cannisters of some kind of bottled gas. First they drop the personnel, and their next assignment is to take about four or five Insignia personnel, including Cruise Director Ray and General Manager Damien plus at least one cameraman out away from the ship to begin creating the 18-minute video of our “Day in a Ditch” as Ray jokingly refers to it. They return and deliver the beer and brochures and, at 6:40, the boat with the Insignia people leaves.

A bit later, another boat pulls alongside and at least a dozen people come out from below and board our ship. These are the line handlers. They will work with the “mule” operators. More on the mules later.

Off in the distance, we can see ships waiting, as well as the Panama City skyline. Our guide explains later that some are waiting to lock through the canal, while others are bunkering (taking on fuel). From what we hear, it cost Oceania Cruises $225,000 for Insignia to go through the canal today. But we also heard that it costs more if a vessel requests a specific time, it varies depending on the carrying capacity of the containership. In other words, tolls are all over the map depending on a bunch of factors, but it ain’t cheap.

Before we proceed with a description of our day, it is probably a good idea to briefly describe the Panama Canal and its operation. Below are two diagrams that I hope will help.

The above shows the canal passage. In our case, we move from right to left, or, put another way, from the Pacific to the Atlantic. The actual direction of the passage we take is northwest. See the map below to see what I mean.

Cruising past Panama City, we will first go through two lock chambers at the Miraflores Locks that will raise the ship. After traversing the 1.2-mile Miraflores Lake, we will go through the one-chamber Pedro Miguel Locks which will complete the 85-foot raising of the ship so that it is even with Gatun Lake. For the next four hours, we will sail 20.3 miles through the lake and 7.8 miles through the Culebra Cut (where we cross the Continental Divide). Next we will go through the three-chamber Gatun Locks, which will drop us down to sea level again. We will proceed past Colon and enter the Atlantic Ocean.

The diagram below describes the locks themselves. The original locks are 1,000 feet long and 110 feet wide, and there are two of them side by side at each location. These have been in operation since 1914. There is now a new set of locks that began operation in 2016, constructed to accommodate the gigantic container ships and cruise ships that are being built today. There is only one lock at each location, and they have a water recycling feature. Because Insignia is only 592 feet long, we can easily be accommodated by the old locks.

The history of the Panama Canal is absolutely fascinating, so we again encourage you to go to YouTube and watch the American Experience video. You will learn that the original plan was to build a sea level canal so there would be no need for locks. Chief Engineer John Stevens told President Theodore Roosevelt that this was impossible (“Mr. President, there are mountains in Panama”) and the plan was redesigned. One of the advantages that made this feasible is that Panama gets a huge amount of rain. Gatun Lake is an artificial lake – the largest one in the world – and has a capacity of 183 billion cubic feet of water. Because, for each ship transiting the canal, 53 million gallons of water end up in the oceans, this rain is a necessity. In fact, sometime toward the end of the four-month dry season, it is necessary to drop the depth of the canal locks to reduce the amount of water being used. That is also the reason for the water-saving basins on the new locks.

I could go on and on about the operation of the canal, and this post will have more info, but we’d better get started on the recap of the day or I will never finish this entry. So we left off with the Insignia video team riding away at 6:40 on the pilot boat. The ship is still a few miles away from the canal. At 8:10, we go up to Pat’s stateroom. As usual, she has gone all out. There is a huge assortment of pastries and rolls, coffee, orange juice and champagne (we contribute a bottle to the cause). Steve is as excited as a child and wants to learn everything possible about this amazing piece of transportation infrastructure, so he immediately goes out with his camera. Soon more people show up, so that there must be fifteen people there by the time we reach the Miraflores Locks.

We pass pleasure boats waiting to transit and sail under the Bridge of the Americas and come upon container ship loading/unloading docks on both sides. As noted above, transiting the Panama Canal is an expensive proposition. But there is a railroad running from the Pacific to the Atlantic that pretty much parallels the canal, and it is cheaper (but of course much slower) to take containers off a ship at one end, transport them by rail to the other end, and the load them on another ship for furtherance to the ultimate destination. So this Maersk ship is at the dock for that purpose.

As we approach the Miraflores Locks, up ahead and to our left, we see a ship locking through the new Cocoli Locks.

When we arrive at the Miraflores Locks, we see a chemical/oil tanker named PAG in the right hand lock, so we are assigned the left hand lock. Because there is no traffic waiting to go in the opposite direction, both locks will be used for Atlantic Ocean-bound ships right now. We spot the Insignia officers and camera crew taking video as we lock through with the tanker.

Getting through both Miraflores lock chambers takes an hour. The ship will move forward under its own power, but it is crucial to keep it precisely in the middle of the lock to prevent damage to the ship or the lock. The ships also need braking control, because a moving ship that could not stop would hit the gates and render the lock useless until the gate was repaired. Those two jobs fall to the “mulas, Spanish for “mules.” These are electric locomotives on a track. On our ship they use two in the bow (one on each side) and two in the stern. On larger ships, they use four and four. First, two men in a rowboat catch the lines thrown from the ship by the canal personnel in the bow and stern that are on board for that purpose. The guys in the rowboat climb off and secure them to the mules. Using bells, the mules on both sides of the canal signal to each other, with radio communication from the pilot in the ship’s bridge. These ships are huge and heavy – even ours at 30,000 tons – and the momentum they possess even at slow speeds is enormous. So everything is very deliberate, which is why it takes an hour to go through the Miraflores Locks.

The 1.2-mile sail through Miraflores Lake takes 45 minutes.

The PAG tanker leaves just ahead of us, accompanied by a tugboat, and will reach the Pedro Miguel Locks just ahead of us as well.

We arrive at 10:45 and are through at 11:15am. PAG is well ahead of us by the time we clear the lock. I have left Pat Watt’s stateroom by this time and take a time lapse video at the Pedro Miguel Locks from our stateroom. Here it is….I hope (I’ve never tried to include video before):

From 11:30 to 12:00, we have lunch at Waves Grill as the ship traverses the Culebra Cut. Here is some info from Wikipedia concerning this part of the canal: “The Culebra Cut, formerly called Gaillard Cut, is an artificial valley that cuts through the Continental Divide in Panama. The cut forms part of the Panama Canal, linking Gatun Lake, and thereby the Atlantic Ocean, to the Gulf of Panama and hence the Pacific Ocean. It is 7.8 miles from the Pedro Miguel lock on the Pacific side to the Chagres River arm of Lake Gatun, with a water level 85 feet above sea level.

Construction of the cut was one of the great engineering feats of its time; the immense effort required to complete it was justified by the great significance of the canal to shipping, and in particular the strategic interests of the United States of America.

Culebra is the name for the mountain ridge it cuts through and was also originally applied to the cut itself. From 1915 to 2000 the cut was named Gaillard Cut after US Major David du Bose Gaillard, who had led the excavation. After the canal handover to Panama in 2000, the name was changed back to Culebra.”

As we dine, we see that a rainstorm is to our stern and is slowly catching up to us. At 12:20, it begins pouring and visibility diminishes significantly.

We pretty much miss viewing the second half of the Culebra Cut. It is still pouring when we go down for a nap, and the rain is still with us at 2:00pm when we wake up. Right then a thunderstorm erupts as we are crossing Gatun Lake.

Steve goes back to Pat Watt’s stateroom at 3:15 to view our passage through the three-lock-chamber Gatun Locks that will lower the ship down 85 feet to sea level. Fortunately the rain has stopped just in time. This process takes until 4:30, and our neighbor in the other lock is the LNG tanker Gas Chem. I shoot a nice time lapse video of it but it’s too long to put on this blog. Cathy is sleeping and then reading all this time.

Steve goes to Horizons a little before 5:00 to buy one of those Panama beers that he saw being transferred from the pilot boat early this morning.

Cathy and I have dinner at Terrace Café that evening around 7:15pm. The ship is in the Atlantic Ocean and Cruise Director Ray has warned us that we will be feeling some ‘motion of the ocean.’ Indeed we do. Time to take advantage of that, so we hit the sack and are rocked to sleep.

This has been a very great learning experience. The Panama Canal was the world’s biggest construction project of its day, and was so well designed and so well constructed that it is still in use today. It was built at a time when America had confidence in its ability to do big things. Despite all the difficulties that were inevitable in a project of this magnitude, the builders prevailed. It is one of our country’s proudest achievements. Given the incessant wrangling, hand-wringing about just about everything, and battalions of environmental lawyers ready to do battle at the first sign of a broken twig, I truly wonder if we still have the ability and tenacity to prevail over the man-made obstacles we put in our own way. It was a great day to see that, at least at one time, we did.

Pat Kohl

July 17, 2018Very interesting and entertaining post, Steve! Loved the movie!